Cancer patient gets one last fishing trip — at Sanford Children’s Hospital

In October, Ethan Erickson lost his life to Burkitt lymphoma. Ethan was 12, just a month shy of 13.

This story won’t dwell on sorrow, though. This story will talk about joy instead.

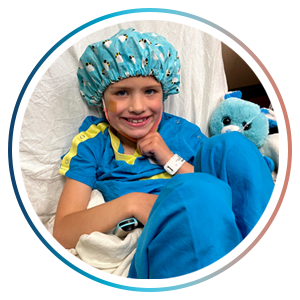

Picture the joy of a boy getting to do something he loves one more time, even if it’s indoors and he’s in a wheelchair, tethered by medical tubing.

And the joy of his parents, watching a smile spread across their son’s face as they all forget, for a while anyway, about his pain and constant battle against an aggressive foe.

Picture the joy of Sanford Health maintenance workers, and South Dakota Game, Fish & Parks workers, interrupting their regular duties to create an unspoken wish come true.

And the joy of the man who quietly loves to mastermind moments of surprise and memories for kids and their families, when he thought of an idea that seemed kind of crazy — and then managed to pull it off just a few hours later.

The way his mom describes Ethan, it seems safe to say he would prefer smiles of joy over tears of sorrow anyway.

Steps forward and back

Ethan was an avid outdoorsman, said his mom, Heather Erickson. He especially loved fishing — catch and release, that is.

Like many other kids, Ethan also enjoyed riding his bike, playing basketball and playing video games at their Hills, Minnesota, home. His brother is several years older; his sister, and frequent companion outdoors, is one year younger.

Ethan had a positive, kindhearted spirit that lasted through even the most difficult times. He showed more concern for his family and his hospital mates than himself, Heather said.

In April 2018, Ethan had stomach surgery for what turned out to be a tumor in his intestines. A biopsy revealed Burkitt lymphoma, a rare but fast-growing B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

After two rounds of chemotherapy at Sanford Children’s Hospital in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, his 30-day scan showed no signs of cancer. The rounds of chemo had been difficult, so the remission was a blessing.

“He had his summer,” Heather said.

He started football and school in the fall of 2018, but a few weeks later, he wasn’t feeling well. His three-month scan then revealed that a tumor had grown in his upper abdomen, hindering his bladder and kidneys. His bone marrow was also 80% affected.

After Ethan spent a month in the ICU on daily dialysis, a round of chemo and steroids, the tumor shrunk enough for his kidneys to start functioning again.

Six rounds of chemo ended in mid-March 2019, but he received a re-diagnosis by the end of April. This time, the cancer was affecting only his bone marrow, so it had become Burkitt leukemia.

After more rounds of chemo, he was set to get a bone marrow transplant over the summer — until blood work shortly before the procedure indicated the bone marrow was up to 40% affected again. His remission had been too short.

Family had a Sanford family

Different types of chemo drugs were used next, in August and September, while Ethan’s oncologist, KayeLyn Wagner, searched for a clinical trial for CAR T-cell therapy — a form of immunotherapy — to enroll him into.

The already limited options for treating Ethan’s aggressive form of cancer were dwindling. “It was like, the minute you didn’t treat it, it would show up again,” Heather said.

Ethan spent a lot of time at Sanford Children’s Hospital receiving treatment. It wasn’t his ideal environment — and it definitely wasn’t the outdoors — but he did enjoy playing Fortnite. From his hospital bed, he could play with friends at their homes, new friends he bonded with at the hospital or his brother at home.

In addition to Ethan’s oncologist, Dr. Wagner, Heather can list many people her family connected with at the hospital, which really had become their second home. From nurses, to child life specialists, to nurse practitioner Ashlee Blumhoff (the family’s “daily network”), to palliative care specialist Dr. Daniel Mark, to kidney disease specialist Dr. Justin Kastl, to Calvin the security guard, to the cafeteria workers who hugged Ethan — they ended up feeling like family to Heather.

Of course, the list wouldn’t be complete without P.T. Dan. The man does have a last name — it’s Steventon — but he considers “P.T. Dan” the important part. The doctor of physical therapy (hence the “P.T.”) helps children undergoing cancer treatments cope with the effects, which can range from weakness to balance problems to cognitive issues.

That’s the basis of the job, but Steventon’s goal there is loftier and simpler at the same time.

“My job gives me this really unique opportunity to create some moments for kids and for their families. … To try to bless kids and help them feel understood,” he said.

Imagine Mr. Rogers crossed with Patch Adams

“If Fred Rogers and Patch Adams rolled around in a dryer for a couple of hours and then came back out as one person,” Steventon said, “I’d like to be that person.”

But think less clown noses, more Scottish accents.

Steventon “tricks” kids into exercise. He acts silly so they forget everything and laugh, rewarding parents who haven’t seen them smile in some time.

He ponders elaborate, meaningful moments — “something that’s going to be mind-blowingly funny” and amaze the whole family.

So he wondered, on a Friday morning in October, how could Ethan catch a fish again? At the hospital? That day?

Steventon first received endorsement from Sanford Children’s nursing director Carol Cressman, who is “usually my partner in crime,” he said.

She made some calls. He made some calls and enlisted the help of Dr. Mark. Within a few hours, maintenance workers had brought a cattle tank into an open area on one floor of the Children’s Hospital and ran hoses to fill it with water. Game, Fish and Parks workers hauled over, in water-filled coolers, three fish from The Outdoor Campus’ aquarium.

Before everything was set, Steventon approached Heather. He gave her an idea of what they were thinking and asked if she thought Ethan would be up for some fishing. After checking that Steventon was serious, she said definitely.

That morning, Ethan was pretty miserable, though he typically never complained. The last rounds of chemo had been tough, and he had spent time in ICU before being moved a few days before to his hospital room. Breathing was difficult, so he was on oxygen; his spleen was enlarged; he had mouth sores.

That morning, Ethan had tried a new kind of chemo intended to attack certain leukemia markers. If it worked, it would give everyone new hope.

‘How do you feel about going fishing?’

When Steventon and Dr. Mark came into his room that afternoon, Ethan was hanging out with his mom and dad watching a movie. He hadn’t stood or walked much in a long time.

Steventon asked, “Hey, Ethan, how do you feel about going fishing today?” But Ethan’s expression of skepticism led Steventon to assure him it wasn’t another one of his games to trick Ethan into therapy.

“His eyes got really wide,” Steventon said.

“He perked right up,” Heather agreed. “… He was like, ‘I can’t believe this is going to happen.’”

So Ethan rode in his wheelchair — accompanied by his medical lines, pumps and monitors — right up to the side of the fish tank and looked inside at the 20-inch bass.

As he watched them, Ethan was asked if he wanted to try catching one, Heather said. “He was just as excited as could be.”

With a nightcrawler as bait, Ethan was handed a pole. But having experienced quite a change in environment, the fish weren’t really in the mood to bite. So a Game, Fish and Parks worker swished the water around a bit and then “helped” the fish find the hook, just out of sight of Ethan.

“When Ethan caught it, he was petting it, like you pet a cat. … He was pretty tired and weak, but he was smiling, and he was reeling. He wasn’t having any problems,” Heather said.

Ethan held the fish up by himself for photos. And he got to catch the other two fish, too.

‘He just lit up’

“I think Dan and Dr. Mark were equally as excited. He just lit up like the smile and joy of the experience was all over his face,” Heather said.

“You’re sitting there thinking, well … it was probably his last chance to catch his fish,” she added.

Steventon, an angler himself, could see and relate to the joy on Ethan’s face. “There’s an authenticity to whenever a fish strikes your hook. When you’re a fisherman, this is the best feeling in the world.”

Ethan hadn’t smiled like that in at least a couple months, his parents told Steventon later.

Maintenance workers had been waiting for Ethan to arrive, Steventon said, “grinning ear to ear” and saying it was the strangest Friday they’d had.

But after Ethan came down, “I look over, these guys are back in the back and they’re just red-faced and wiping tears out of their eyes,” Steventon said. “I’m like, I made everybody cry.”

During the planning and participation in moments like this, Steventon is too driven to really feel the weight of it until a couple hours later.

“Then it hits me like a truck, and I cry a lot in my car,” Steventon said. “But it’s better than crying in the building. I try not to cry in the building as much. My truck can take it.”

‘The timing could not have been more ordained’

When Ethan got back to his room, after saying, “Goodbye, fishies,” he stood up and walked over to the sink to wash his hands. When he sat down again, he grinned and thanked Steventon. Steventon told him he loved him and asked if Ethan had fun.

“Oh, yeah,” Ethan replied.

“I’ve learned to tell my patients that I love them,” Steventon said later, “especially when I’m not sure when I’m going to see them again.”

Heather said Ethan talked about the fishing trip the rest of that day. “I can’t believe they brought those big fish here,” he kept saying to his parents.

On Sunday of that weekend, Steventon received news he wasn’t expecting.

Ethan had died early that morning.

Among the feelings that came over him was relief they had been able to pull off the fishing trip on Friday — that he’d insisted it had to be that day, and that Game, Fish and Parks had been able to make it work.

“The timing could not have been more ordained,” Steventon said. “It was perfect.”

When Steventon went to Ethan’s visitation, Ethan’s parents spotted Steventon in line. “They ran up and hugged me and told me that that was the best day,” he said. “That was their favorite memory of all of the hospital stuff. So that’s what sticks with me.”

Continuing Ethan’s positivity

Ethan didn’t want his family to cry when they were with him. “We’re not doing that today,” he would say.

So while his November birthday and holidays represent difficult moments, Heather doesn’t dwell on them.

“I just feel like that’s the best way to maintain Ethan’s positive spirit and move forward, is to keep that positivity and remember the good memories,” she said.

“Hopefully we can find a way to pay back kindness.”

Heather and her husband, Aaron, were grateful to return to the Sanford hospital campus recently with their daughter for the monthly Hero awards ceremony. This time, the ceremony recognized everyone who had been involved in making Ethan’s special memory happen. When the family found out that another award recipient would be George the therapy dog — beloved by Ethan and his sister — “it was perfect,” Heather said.

“I always feel overwhelmed about how to show thanks … so I tried to use that opportunity to thank everyone on our team,” she said. She talked about Ethan and what his hospital team meant to their family.

Hopefully, as Steventon stood up with the others who were recognized that day, he felt the answer come to a question that he asks himself about all of the kids he works with, and as he tries to find that special thing that matters to each one:

“Did I make a difference?”

And, “did they understand that I think that they are precious?”

But Steventon relishes the fact that he gets to show kids how to beat what looks like unbeatable obstacles. He gets to think ahead of their fears and help solve problems they don’t know they’ll have. He gets to be the person families can count on as an advocate.

“There’s joy in knowing that you made a difference,” he said.

Story from https://news.sanfordhealth.org/